“I’m an engineer. Not an environmentalist,” says Michael Polsky, as if to explain why even after spending 17 years developing renewable-energy systems, he’s still enthralled by the sight of 125-foot-long wind turbine blades sweeping in elegant circles through the sky. It’s machines that this serial entrepreneur loves. And building. And making profitable deals. After becoming a centimillionaire by developing gas-fired turbines, the 71-year-old has ridden wind power to billionaire status.

We’re touring the Grand Ridge Energy Center, a renewable energy complex that Polsky’s private company, Invenergy, built and owns 80 miles southwest of its Chicago headquarters. He eagerly shows off his 140 wind turbines, 120 acres of solar panels and a utility-scale battery installation that in an emergency can put out 38 megawatts (enough to power about 38,000 homes) for an hour. Then the slim septuagenarian with a mop of curly gray hair strides toward a row of new “bi-facial,” or double-sided, photovoltaic panels, which also catch sun rays bouncing off the ground, generating 8% more power on the same square footage as conventional solar panels. “The technology is so good and ripe. You get the conviction that it has to happen,’’ Polsky says in his slight Ukrainian accent. “The revolution has been won.”

YOU HAVE ONLY YOURSELF TO BLAME

One big obstacle to green energy is spelled y-o-u. Technological advances have made wind and solar power cheaper than coal, nuclear and even natural gas. So why aren’t we using more of the stuff? Quite simply because you (and your neighbors) oppose and block the construction of wind farms and new transmission lines for green power.

The technological revolution, that is. Even without tax breaks, wind and solar power are now cheaper than fossil fuels, a stunning turnabout in just the last decade (see chart). President-elect Joe Biden wants to renew soon-to-expire clean-energy tax credits. Plus, part of his $2 trillion climate plan is a pledge to install 60,000 wind turbines and 500 million solar panels over the next five years to achieve a carbon-free power grid by 2035. A Republican Senate would likely block most of that spending.

No matter. With cities, states and corporations setting their own “net zero carbon” goals, the demand for industrial-scale solar and wind power, which now account for just 12% of domestic power supply, will continue to surge. Polsky is buying turbines from GE Power that are twice the size of those at Grand Ridge (at 700 feet, they’re taller than Trump Tower in New York) and generate up to 3 megawatts each. He intends to erect more than 1,000 of these enormous machines on 100,000 acres in Kansas, on what could become the nation’s biggest wind farm.

While the technological revolution has been won, Polsky still needs to get his windmills sited and to transport the wind power to the people. On that front, skirmishes continue. Farmers are not thrilled about the prospect of Invenergy using eminent domain laws to claim a right-of-way corridor through their land for an 800-mile-long, $7 billion high-voltage transmission line (called the Grain Belt Express) that would move power from Kansas through Missouri to Illinois. Fights against wind farms have broken out recently from ruby-red Wyoming to solid-blue Santa Barbara.

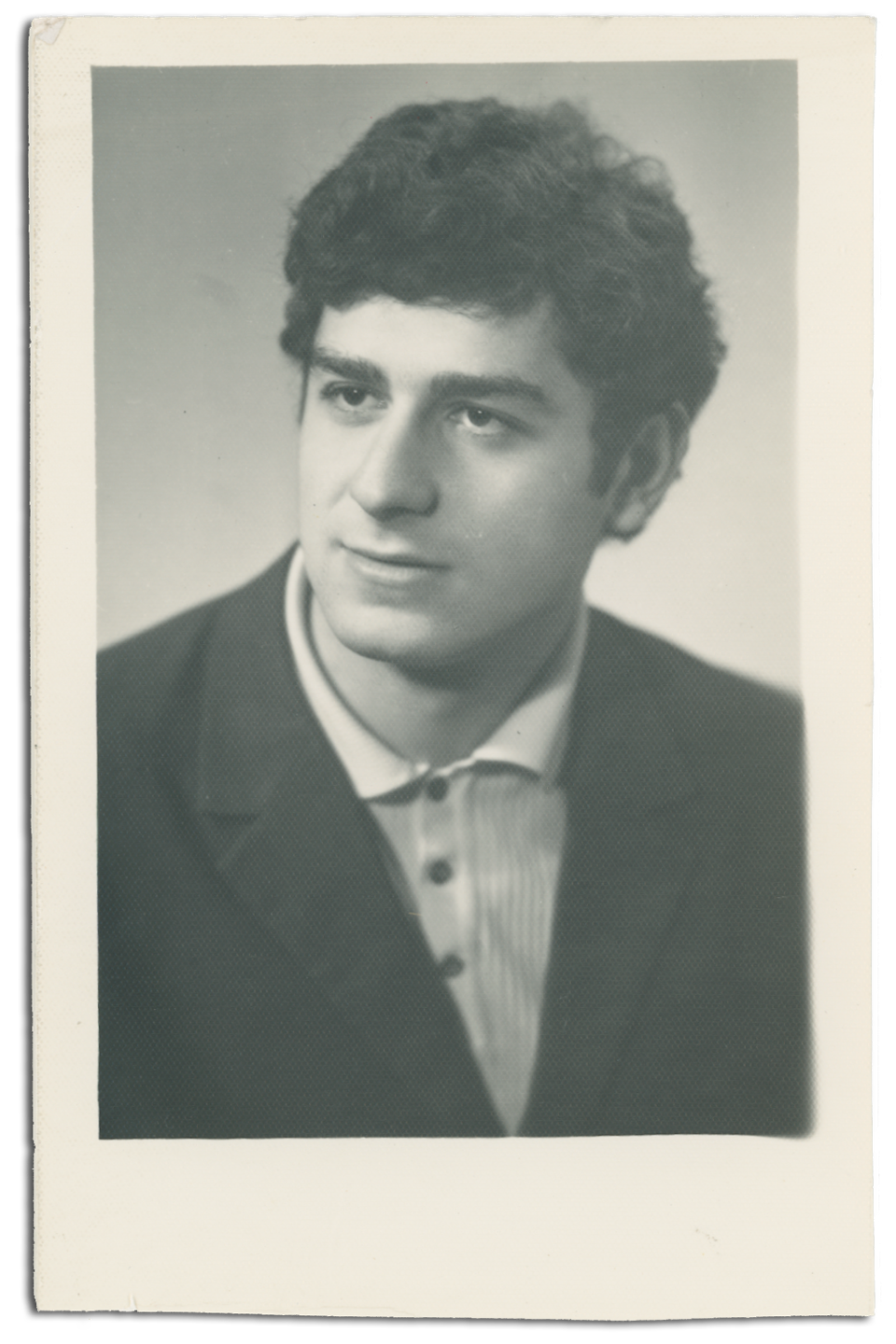

The Young Engineer: After Kiev Polytechnic Institute, dim job prospects in the Soviet bloc drove Polsky to America.

INVENERGY

The irony here is that hard-nosed, profit-driven developers like Polsky, ready to bulldoze, litigate and lobby through such not-in-my-backyard objections, are key to realizing the world’s clean-energy future. “It is not going to happen just because we want it to,” Polsky warns.

In 1976, the then-26-year-old Polsky and his pregnant wife, Maya, who taught English when the couple lived in Ukraine, arrived in Detroit with $500 and four suitcases of belongings. He had a master’s in mechanical engineering from top-notch Kiev Polytechnic Institute, but as a Jew, saw little future for himself in Soviet Ukraine. The charity that had helped to resettle the couple in Detroit suggested Polsky take a blue-collar job. Instead, he sent out hundreds of résumés and, despite his limited English skills, landed an engineering job at a Bechtel power plant, later moving to ABB and Fluor.

Back then, smoke-belching, coal-burning plants were state of the art in the heavily regulated power business. But a big opportunity was emerging: In 1978, Congress partially deregulated the power industry, enabling independent startups to build plants and sell juice to the grid.

That change enabled Polsky, a Ukrainian engineer, to transform himself into an American dealmaker. In 1985, he and a partner launched Indeck Energy Services to develop cogeneration projects, in which steam produced as a by-product of power generation is used to run industrial plants. While earning an M.B.A. at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, Polsky traveled the country, selling cogeneration to the likes of DuPont.

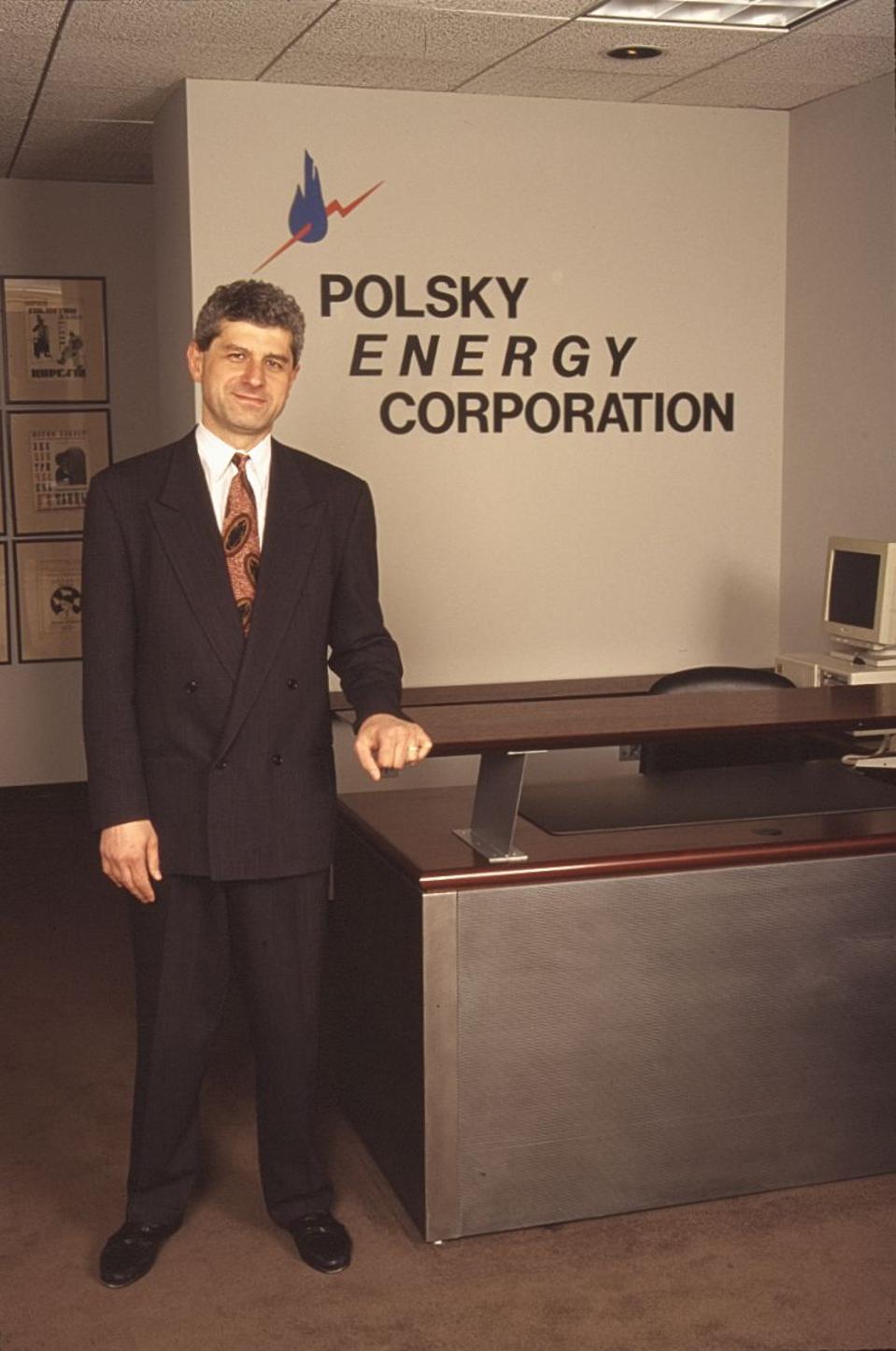

Indeck was successful, but the partnership soured and Polsky was ousted. He sued and ended up with a $25 million settlement. In 1991 he launched Polsky Energy, later renamed SkyGen, which specialized in building gas-fired generators that could ramp up rapidly to provide power for top dollar at times of peak demand. A decade later, Polsky sold SkyGen to publicly traded Calpine for $450 million net of debt; he got about half of that.

In 1991, after an acrimonious split with his first business partner, Polsky launched an eponymous energy company in Chicago to build gas-fired power plants, later rebranding it SkyGen.

INVENERGY

He was now a centimillionaire, but frustrated to be cooling his heels on the board of Calpine instead of making deals and running his own show. So he resigned, taking four SkyGen colleagues with him to start Invenergy with $75 million of his own capital.

Polsky’s original plan was to stick to natural gas, but there was a glut of such plants. (Calpine itself filed for bankruptcy protection in 2005 with $17 billion in debt.) And so, in 2003, Invenergy stuck a finger up to gauge the wind business, first building a disappointing small project for the Tennessee Valley Authority. It ran over budget and, it turned out, was situated in a spot in the Blue Ridge Mountains where the wind didn’t blow hard enough. Lessons learned, Invenergy’s next projects, located in windier parts of Montana, Colorado and Idaho, were many times bigger—and profitable.

By 2006, Polsky was worth $367 million—according to an Illinois court that ordered him to hand over half of it to Maya, who had filed for divorce. While Polsky unsuccessfully appealed the order, complaining (among other things) that he was being forced to liquidate assets to pay her, it didn’t set back his dealmaking and wealth-building for long.

To date, Invenergy and its subsidiaries have built 160 projects totaling 25,000 megawatts of wind, solar and natural-gas generation—enough to power 5 million homes. Polsky has sold about 55% of that capacity to a big Canadian pension fund and other investors, although in some cases Invenergy still runs the projects. “The best way to grow is to recycle capital into new projects,” Polsky says. “We sell assets to raise money to keep control. I could have raised more money if I gave up control, but I never wanted to give up control.”

“Hard-nosed, profit-driven developers are key to realizing the world’s clean-energy future.”

While Polsky won’t provide financial details for privately held Invenergy, analysts figure the whole enterprise is worth around $10 billion. After deducting for joint-venture interests and presumed debt loads, Forbes estimates Polsky’s controlling stake gives him a net worth of $1.5 billion. Invenergy is now the second-largest producer of wind power in the U.S.—second, that is, to NextEra Energy, a publicly traded utility holding company with a market cap of $150 billion.

Back in Chicago, Polsky leads an impromptu tour of the three floors Invenergy occupies at One South Wacker Drive in the pandemic ghost town that is downtown Chicago. It’s a Friday morning. Ordinarily, there would be dozens of people in open-plan workstations and offices, but only a handful are present, including the 24/7 crew manning Invenergy’s control center—watching, and even operating, 6,774 wind turbines spread across the country.

Sharing Invenergy’s digs are the offices of Polsky’s $150 million green-tech-focused VC fund, Energize Ventures. Among its 13 portfolio investments: Drone Deploy, which inspects turbine blades using infrared beams and drones, and Volta, which is building a chain of electric vehicle charging stations.

These days, Polsky has reluctantly traded the standing desk in his office for Zoom calls from his living room and quality time with his second wife, Tanya, 47, a former banker, and their three young children. “I’ve spent a lot more time with family than before,” the compulsive dealmaker admits. He seems to be enjoying it. “I’ve discovered being home, in a way.”

Polsky’s battles to build say a lot about both the political challenges facing wind power and the wily, pragmatic operator he has become. His most ambitious project to date was Wind Catcher, designed to create 2,000 megawatts of capacity from 800 turbines in Oklahoma at a cost of $4.5 billion. Invenergy broke ground in 2016 but stopped work when Texas regulators, egged on by antiwind groups like the Windfall Coalition (backed by fracking billionaire Harold Hamm), blocked the project, saying it wouldn’t sufficiently benefit rate payers. Undeterred, Invenergy and its partner, utility giant American Electric Power, are now building $2 billion worth of Oklahoma wind farms to serve that state and parts of Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas.

Then there’s that Grain Belt Express, which would install an 800-mile high- voltage line across Kansas and Missouri into Illinois at a cost of $7 billion. It was originally the brainchild of wind-industry pioneer Michael Skelly, whose Clean Line Energy was backed by the billionaire Ziff family, among others. Skelly’s team burned through $100 million fighting NIMBys and bureaucrats in its quest for permits and approvals. “After a decade, it was hard for us to attract capital,” says Skelly, now a senior advisor at Lazard.

An eagle-eye view: Polsky’s Invenergy owns or operates nearly 7,000 turbines, worldwide.

INVENERGY

Polsky agreed to take over Grain Belt on the condition of Invenergy winning those approvals—in other words, all he risked upfront was the cost of lawyers and lobbyists. “It’s much more complicated than just building a wind farm,” admits Polsky, who relishes the challenge. A bill that would keep non-utility companies like Invenergy from using eminent domain to take private land passed the Missouri state assembly this year but has been bottled up in the state senate. Meanwhile, two Missouri appeals courts have upheld the state public service commission’s approval of the Grain Belt Express.

Despite ongoing appeals, farmers like Loren Sprouse, whose family owns a 480-acre tract west of Kansas City that the high-voltage line would cross, are becoming resigned to the fact that soon Invenergy will be able to negotiate with the sledgehammer of eminent domain. “Once you get eminent domain, the price may still be negotiated, but they would have the right to do it,’’ he says.

Sprouse’s land is already crossed by three buried petrochemical pipelines, which he says transport warmed crude that “runs so hot it dries out the ground and kills the crops.” (Indeed, the proposed transmission lines would run along the pipeline right-of-way.) But Sprouse prefers the pipelines to the visual blight of hulking transmission lines, and he’s concerned about the health effects of electromagnetic radiation. Polsky is encouraged by Invenergy’s legal victories in Missouri, and expects Illinois approvals to follow. “It will be built. It has to happen,” he says.

The full range of competing interests—and Polsky’s tactics—are on display in his battle in New York’s rural Allegheny and Cattaraugus counties, east of Lake Erie. There, Invenergy is moving through the permitting process on its proposed Alle-Catt Wind Farm, which would spread 117 turbines across 30,000 acres south of Buffalo, with a maximum output of 340 megawatts.

“Sure, Polsky’s turbines will chop up eagles and bats, but they won’t put mercury, cadmium, sulfur dioxide or CO2 into the air.”

Farmers from the Old Order Amish Swartzentruber sect moved to the region in 2011 in search of a life removed from modern technology. They and other landowners object to the size of the turbines, their noise, their red blinking lights at night and the strobelike effect caused by the sun rising or setting behind the spinning blades.

“Their religious beliefs dictate that they don’t live near industrial development,” says the sect’s attorney, Gary Abraham. They asked the state siting board to grant them a 2,200-foot setback between the turbines and their homes and barns, arguing they are the community’s de facto churches. But the board ruled they were entitled only to the normal 1,500-foot residential setback, not the 2,200-foot one churches get, and ignored other local opposition. “They are experts in sweet-talking landowners into parting with their land,” Abraham says of Invenergy. “There’s no green in their body except for the dollar.” The outflanked Amish have started looking upstate for new land.

To be sure, Invenergy’s tactics have drawn scrutiny. Last year, New York’s attorney general fined it $25,000 for undisclosed conflicts of interest—Invenergy had pushed through favorable new wind laws in the towns of Freedom and Farmersville without disclosing that it had signed land leases with certain town employees and officials. Attorney Ginger Schroder, who raises heritage exotic poultry in Farmersville, was outraged, and organized citizens to unseat those officials in 2019. The new regime’s first act upon taking office was to undo the Invenergy-friendly rules passed by its predecessor—like the one that increased the permissible noise from turbines.

Schroder is also supporting Abraham’s suit against the New York renewable-energy siting board that aims to overturn its approval of Alle-Catt. Invenergy has “a very determined single-purpose perspective, ignoring laws and communities and all sorts of outcry,’’ she says.

Polsky doesn’t deny that his single-minded pursuit is to build. “Nobody ever built renewables because they need electricity,” he says. “You build to replace something else.” In this case, he’s replacing New York’s last coal-fired power plant, a 686-megawatt unit near Buffalo that closed in March 2020. Over its 30-year lifespan, Alle-Catt’s turbines are projected to chop up 41 bald eagles and thousands of bats. But they will not put mercury, cadmium, sulfur dioxide or CO2 into the air. Polsky doesn’t doubt that the benefits of replacing coal emissions outweigh the eagles lost or the disruption for Amish and other farmers.

“If you’re just making money, you can only go so far,’’ he says. “When you have a mission, a conviction, you perform on a completely different level. You believe so strongly, you don’t take no for an answer.”